Working with Slices in Go (Golang) - Understanding How append, copy and Slice Expressions Work

Related Posts

Content

Introduction

Go programming language has two fundamental types at the language level to enable working with numbered sequence of elements: array and slice. At the syntax level, they may look like the same but they are fundamentally very different in terms of their behavior. The most critical fundamental differences are:

- Size of the array is fixed and determined at the construction (as you may expect). However, slices can dynamically grow in size (you may wonder how? We will touch on this soon, be patient!)

- An array with a specific length is a distinct type based on its length (check this out). Whereas the slice can be represented as one type (e.g.

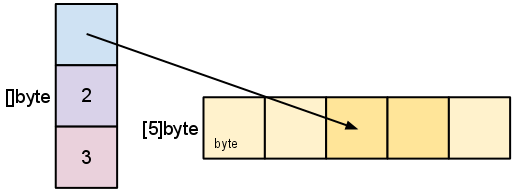

[]int) - The in-memory representation of an array type is values laid out sequentially. A slice is a descriptor of an array segment. It consists of a pointer to the array, the length of the segment, and its capacity (we will shortly see what this actually means).

- Go's arrays are values, which means that the entire content of the array will be copied when you start passing it around. Slices, on the other hand, a pointer to the underlying array along with the length of the segment. So, when we started passing around a slice, it creates a new slice value that points to the original array, which will be much cheaper to pass around.

Above points highlight some characteristics of slices and how they differ from arrays, but these are mostly differences in terms of how they are structured. More interesting and unobvious differences of slices are around their behaviors around manipulations.

How Slices Work

To be able to understand how slices works, we first need to have a good understanding of how arrays work in Go, and you can check out this informative description to gain more understanding on arrays than the above summary.

Slices are the constructs in Go which give us the flexibility to work with dynamically sized collections. A slice is an abstraction of an array, and it points to a contiguous section of an array stored separately from the slice variable itself. Internally, a slice is a descriptor which holds the following values:

- pointer to the backing array (actually, pointer to the array value which indicates 0th index of the slice, which we will cover later)

- the length of the segment it's referring to

- its capacity (the maximum length of the segment)

There are various ways how you can define a slice in Go, and all of the following ways leads to the same outcome: a slice with a zero length and capacity

func main() {

var a []int

b := []int{}

c := make([]int, 0)

fmt.Printf("a: %v, len %d, cap: %d\n", a, len(a), cap(a))

fmt.Printf("b: %v, len %d, cap: %d\n", b, len(b), cap(b))

fmt.Printf("c: %v, len %d, cap: %d\n", c, len(c), cap(c))

}

a: [], len 0, cap: 0 b: [], len 0, cap: 0 c: [], len 0, cap: 0

You can also initialize a slice with seed values, and the length of the values here will also be the capacity of the backing array:

func main() {

a := []int{1,2,3}

fmt.Printf("a: %v, len %d, cap: %d\n", a, len(a), cap(a))

}

a: [1 2 3], len 3, cap: 3

In case you know the maximum capacity that a slice can grow to, it's best to initialize the slice by hinting the capacity so that you don't have to grow the backing array as you add new values to slice (which we will see how to in the next section). You can do so by passing it to the make builtin function.

func main() {

a := make([]int, 0, 10)

fmt.Printf("a: %v, len %d, cap: %d\n", a, len(a), cap(a))

}

a: [], len 0, cap: 10

This still doesn't mean that you can access the backing array freely by index, as the length is still 0. If you attempt to do so, you will get "index out of range" runtime error.

How append and copy Works

When we want to add a new value to an existing slice which will mean growing its length, we can use append, which is a built-in and variadic function. This function appends elements to the end of a slice, and returns the updated slice.

func main() {

var result []int

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if i % 2 == 0 {

result = append(result, i)

}

}

fmt.Println(result)

}

As you may expect, this prints [0 2 4 6 8] to the console as a result. However, it's not clear here what exactly is happening underneath as a result of invocation of the append function, and what the time complexity of the call is. When we run the below code, things will be a bit more clear to us:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"reflect"

"unsafe"

)

func main() {

var result []int

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if i % 2 == 0 {

fmt.Printf("appending '%d': %s\n", i, getSliceHeader(&result))

result = append(result, i)

fmt.Printf("appended '%d': %s\n", i, getSliceHeader(&result))

}

}

fmt.Println(result)

}

// https://stackoverflow.com/a/54196005/463785

func getSliceHeader(slice *[]int) string {

sh := (*reflect.SliceHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(slice))

return fmt.Sprintf("%+v", sh)

}

appending '0': &{Data:0 Len:0 Cap:0}

appended '0': &{Data:824633901184 Len:1 Cap:1}

appending '2': &{Data:824633901184 Len:1 Cap:1}

appended '2': &{Data:824633901296 Len:2 Cap:2}

appending '4': &{Data:824633901296 Len:2 Cap:2}

appended '4': &{Data:824633803136 Len:3 Cap:4}

appending '6': &{Data:824633803136 Len:3 Cap:4}

appended '6': &{Data:824633803136 Len:4 Cap:4}

appending '8': &{Data:824633803136 Len:4 Cap:4}

appended '8': &{Data:824634228800 Len:5 Cap:8}

[0 2 4 6 8]

We can extract the following facts from this result:

nilslice starts off with empty capacity, nothing surprising with that- The capacity of the slice doubles while attempting to append a new item when its capacity and length are equal

- When the capacity is doubled, we can also observe that the pointer to the backing array (i.e. the

Datafield value ofreflect.SliceHeaderstruct) changes

In summary, it's a fair to assume from these facts that the content of the backing array of the slice is copied into a new array which has double capacity than the itself when it's being attempted to append a new item to it while its capacity is full. It should go without saying that the implementation is a bit more complicated than this as you may expect, and this post from Gary Lu does a good job on explaining the implementation details in more details. You can also check out the growSlice function which is used by the compiler generated code to grow the capacity of the slice when needed.

In a nutshell, this is not a good news to us since we are doing too much more work than it's worth. In these cases, initializing the array with the make built-in function is a far better option with a capacity hint based on the max capacity that the slice can grow to:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"reflect"

"unsafe"

)

func main() {

maxValue := 10

result := make([]int, 0, maxValue)

for i := 0; i < maxValue; i++ {

if i % 2 == 0 {

fmt.Printf("appending '%d': %s\n", i, getSliceHeader(&result))

result = append(result, i)

fmt.Printf("appended '%d': %s\n", i, getSliceHeader(&result))

}

}

fmt.Println(result)

}

// https://stackoverflow.com/a/54196005/463785

func getSliceHeader(slice *[]int) string {

sh := (*reflect.SliceHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(slice))

return fmt.Sprintf("%+v", sh)

}

appending '0': &{Data:824633794640 Len:0 Cap:10}

appended '0': &{Data:824633794640 Len:1 Cap:10}

appending '2': &{Data:824633794640 Len:1 Cap:10}

appended '2': &{Data:824633794640 Len:2 Cap:10}

appending '4': &{Data:824633794640 Len:2 Cap:10}

appended '4': &{Data:824633794640 Len:3 Cap:10}

appending '6': &{Data:824633794640 Len:3 Cap:10}

appended '6': &{Data:824633794640 Len:4 Cap:10}

appending '8': &{Data:824633794640 Len:4 Cap:10}

appended '8': &{Data:824633794640 Len:5 Cap:10}

[0 2 4 6 8]

We can observe from the result here that we have been operating over the same backing array with the size of 10, which means that all the append operations have run in O(1) time.

There is also another built-in function which makes it easy to transfer values from one slice to another: copy. I will quote the definition of copy straight from the Go spec:

"The function copy copies slice elements from a sourcesrcto a destinationdstand returns the number of elements copied. Both arguments must have identical element typeTand must be assignable to a slice of type[]T. The number of elements copied is the minimum oflen(src)andlen(dst)."

It's probably obvious, but still worth mentioning that copy runs in O(N) time, where N is the number of elements it can copy. The following example demonstrates copy function in action:

func main() {

a := make([]int, 5, 6)

b := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

fmt.Println(copy(a, b))

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

}

5 a: [1 2 3 4 5], cap: 6

How Slice Expressions Work

Slice expressions construct a substring or slice from a string, array, pointer to array, or slice (e.g. a[1:5]). The result has indices starting at 0 and length equal to high - low. This is great, as it gives us an easy way to perform slicing operations on the original value, and this is being performed super efficiently. The reason for this is that slicing does not result in copying the slice's data. It creates a new slice value (i.e. reflect.SliceHeader) that points to the original array (it's actually the pointer to the first element of the new slice):

The following example should be able to demonstrate this behavior for us:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"reflect"

"unsafe"

)

func main() {

maxValue := 10

result := make([]int, 0, maxValue)

for i := 0; i < maxValue; i++ {

if i % 2 == 0 {

result = append(result, i)

}

}

for i := range result {

fmt.Printf("%d: %v\n", i, &result[i])

}

newSlice := result[1:3]

newSlice2 := result[2:4]

fmt.Printf("[:]: %s\n", getSliceHeader(&result))

fmt.Printf("[1:3]: %s\n", getSliceHeader(&newSlice))

fmt.Printf("[2:4]: %s\n", getSliceHeader(&newSlice2))

}

func getSliceHeader(slice *[]int) string {

sh := (*reflect.SliceHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(slice))

return fmt.Sprintf("%+v", sh)

}

Let's unpack what we are doing here:

- we are creating a slice

- filling it with data and printing the hexadecimal representation of a memory address of each value in the slice (so that we can compare these later)

- slicing it twice, and assigning the new slices to separate variables

- inspecting the header values of each slice

The outcome is as below (you can also run it here):

0: 0xc000012050

1: 0xc000012058

2: 0xc000012060

3: 0xc000012068

4: 0xc000012070

[:]: &{Data:824633794640 Len:5 Cap:10}

[1:3]: &{Data:824633794648 Len:2 Cap:9}

[2:4]: &{Data:824633794656 Len:2 Cap:8}

As a result, we are seeing that [1:3] slice has the length 2 (which is expected). What's interesting is the capacity which is 9. The reason for that is that the capacity assigned to the sliced-slice is influenced by the starting point of the new slice (i.e. low) and the capacity of the original slice cap, and calculated as cap - low, and the rest of the capacity is referring to the same sequential dedicated memory addresses of the backing array. We will see in the next sections what the implications of this behavior can be.

The other interesting thing we are seeing here is that the pointer to the backing array has changed. This is the result of the memory representation of the array. An array is stored as a sequence of n blocks of the type specified. So, the pointer here is actually pointing to the 1st index value of the original array, which we can confirm by comparing the hexadecimal representation of a memory address of each value in the original slice: [1:3] slice is pointing to 824633794648 and 1st indexed value in the original slice is pointing to 0xc000012058 which is the hexadecimal value of 824633794648.

The similar story is there for the [2:4] sliced-slice, too. What we can confirm from this is that slicing is super efficient with the cost of sharing the backing array with the original slice.

⚠️ Modifying a Sliced-slice Modifies the Original Slice

By looking at the internals of how slicing works, we have seen that the new slice, which is returned by slicing an existing slice, is still referring to the same backing array as the original slice. This introduces a very interesting implication that modifying data on the indices of the newly sliced-slice also causes the same modification on the original slice, which can actually cause very hard to track down bugs, and the following code snippet is showing how this can happen:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

a := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b := a[2:4]

b[0] = 10

fmt.Println(b)

fmt.Println(a)

}

[10 4] [1 2 10 4 5]

In this given example, the issue may already be apparent to us. However, this unobvious behavior of how slicing works underneath (to be fair, for the right performance reasons) can make some issues more obfuscated when the slicing and modification is done in different places. For instance, with the following example (which you can also see here), we can see that Result method on the race instance is not returning the expected result anymore due to the modifications done to the slice returned by the Top10Finishers method, because sort.Strings call modified the array which is actually backing the both slices.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"play.ground/race"

"sort"

)

func main() {

belgium2020Race := race.New("Belgian", []string{

"Hamilton", "Bottas", "Verstappen", "Ricciardo", "Ocon",

"Albon", "Norris", "Gasly", "Stroll", "Perez",

"Kvyat", "Räikkönen", "Vettel", "Leclerc", "Grosjean",

"Latifi", "Magnussen", "Giovinazzi", "Russell", "Sainz",

})

top10Finishers := belgium2020Race.Top10Finishers()

sort.Strings(top10Finishers)

fmt.Printf("%s GP top 10 finishers, in alphabetical order: %v\n", belgium2020Race.Name(), top10Finishers)

fmt.Printf("%s GP result: %v\n", belgium2020Race.Name(), belgium2020Race.Result())

}

-- go.mod --

module play.ground

-- race/race.go --

package race

type race struct {

name string

result []string

}

func (r race) Name() string {

return r.name

}

func (r race) Result() []string {

return r.result

}

func (r race) Top10Finishers() []string {

return r.result[:10]

}

func New(name string, result []string) race {

return race{

name: name,

result: result,

}

}

Belgian GP top 10 finishers: [Hamilton Bottas Verstappen Ricciardo Ocon Albon Norris Gasly Stroll Perez] Belgian GP top 10 finishers, in alphabetical order: [Albon Bottas Gasly Hamilton Norris Ocon Perez Ricciardo Stroll Verstappen] Belgian GP result: [Albon Bottas Gasly Hamilton Norris Ocon Perez Ricciardo Stroll Verstappen Kvyat Räikkönen Vettel Leclerc Grosjean Latifi Magnussen Giovinazzi Russell Sainz]

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the the problem here. It will really depend on your usage, and what type of contract you are exposing from your defined type. If you are after creating a domain model encapsulation where you don't want to allow unmodified access to the state of that model, you can instead make a copy of the slice that you want to return, with the cost of extra time and space complexity you are introducing. The following code shows the only modification we would have done to the above example to make this work:

func (r race) Top10Finishers() []string {

top10 := r.result[:10]

result := make([]string, len(top10))

copy(result, top10)

return result

}

When we execute this version of the implementation, we can now see that the sort.Strings call is not implicitly modifying the original slice:

Belgian GP top 10 finishers: [Hamilton Bottas Verstappen Ricciardo Ocon Albon Norris Gasly Stroll Perez] Belgian GP top 10 finishers, in alphabetical order: [Albon Bottas Gasly Hamilton Norris Ocon Perez Ricciardo Stroll Verstappen] Belgian GP result: [Hamilton Bottas Verstappen Ricciardo Ocon Albon Norris Gasly Stroll Perez Kvyat Räikkönen Vettel Leclerc Grosjean Latifi Magnussen Giovinazzi Russell Sainz]

Another option here is to expose a read-only version of the data, which you can achieve by encapsulating the slice behind an interface. This would only allow certain read-only operations, and make it more obvious to the consumer of the package what's the cost of the operation is:

type ReadOnlyStringCollection interface {

Each(f func(i int, value string))

Len() int

}

This forces your consumer to iterate over the data first before attempting to manipulate it, which is positive from the point of establishing a much more clear contract from your package. The following is showing how you can implement this inside the race package:

-- race/race.go --

package race

type race struct {

name string

result []string

}

func (r race) Name() string {

return r.name

}

func (r race) Result() []string {

return r.result

}

func (r race) Top10Finishers() ReadOnlyStringCollection {

return readOnlyStringCollection{r.result[:10]}

}

func New(name string, result []string) race {

return race{

name: name,

result: result,

}

}

type readOnlyStringCollection struct {

value []string

}

func (r readOnlyStringCollection) Each(f func(i int, value string)) {

for i, v := range r.value {

f(i, v)

}

}

func (r readOnlyStringCollection) Len() int {

return len(r.value)

}

type ReadOnlyStringCollection interface {

Each(f func(i int, value string))

Len() int

}

The following is how you can now make use of it:

func main() {

belgium2020Race := race.New("Belgian", []string{

"Hamilton", "Bottas", "Verstappen", "Ricciardo", "Ocon",

"Albon", "Norris", "Gasly", "Stroll", "Perez",

"Kvyat", "Räikkönen", "Vettel", "Leclerc", "Grosjean",

"Latifi", "Magnussen", "Giovinazzi", "Russell", "Sainz",

})

top10Finishers := func() []string {

result := make([]string, 10)

top10 := belgium2020Race.Top10Finishers()

top10.Each(func(i int, val string) {

result[i] = val

})

return result

}()

fmt.Printf("%s GP top 10 finishers: %v\n", belgium2020Race.Name(), top10Finishers)

sort.Strings(top10Finishers)

fmt.Printf("%s GP top 10 finishers, in alphabetical order: %v\n", belgium2020Race.Name(), top10Finishers)

fmt.Printf("%s GP result: %v\n", belgium2020Race.Name(), belgium2020Race.Result())

}

When we execute this version of the implementation, we can now see that the sort.Strings call is not implicitly modifying the original slice in this case, too:

Belgian GP top 10 finishers: [Hamilton Bottas Verstappen Ricciardo Ocon Albon Norris Gasly Stroll Perez] Belgian GP top 10 finishers, in alphabetical order: [Albon Bottas Gasly Hamilton Norris Ocon Perez Ricciardo Stroll Verstappen] Belgian GP result: [Hamilton Bottas Verstappen Ricciardo Ocon Albon Norris Gasly Stroll Perez Kvyat Räikkönen Vettel Leclerc Grosjean Latifi Magnussen Giovinazzi Russell Sainz]

⚠️ Calling append on a Sliced Slice May Modify the Original Slice

We have previously went over how append function in Go works by appending elements to the end of a slice, and returning the updated slice. This can sort of give you the impression that the append function is a pure function, and doesn't modify your state. However, we have seen from how append works that it may not be the case. If we combine this with the fact that the new slice, which is returned by slicing an existing slice, is still referring to the same backing array as the original slice, following example demonstrates a behavior which is a bit more unobvious than the above one:

func main() {

a := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b := a[2:4]

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

b = append(b, 20)

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

}

a: [1 2 3 4 5], cap: 5 b: [3 4], cap: 3 b: [3 4 20], cap: 3 a: [1 2 3 4 20], cap: 5

In this example, we have a slice assigned to variable a, and we slice this array to assign a new slice to variable b. We print the results. We see that our sliced-slice has a length of 2, and capacity of 3. All good, expected. However, interesting behavior kicks in when we attempt to append a value to slice b. The append works as expected, and the slice b has the new appended value. Besides that, we can see from the result of our code that slice a has also been modified, and the original value on the 4th index (i.e. 5) is now replaced with 20 which was the value appended to slice b.

The reason for this behavior is exactly reasons we have talked about before. The remaining capacity of the sliced-slice is still also being used by the original slice. To be frankly honest, it would be unfair to call this an unexpected behavior since it's documented in a detailed fashion. Nevertheless, this would be fair to classify this as an entirely unobvious behavior especially if you are new to the language, and expect the code to highlight a bit more of its behavior.

The only time you wouldn't have the same behavior here is where the sliced-slice's capacity was already full right after slicing:

func main() {

a := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b := a[2:]

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

b = append(b, 20)

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

}

a: [1 2 3 4 5], cap: 5 b: [3 4 5], cap: 3 b: [3 4 5 20], cap: 6 a: [1 2 3 4 5], cap: 5

In this example, we can see that the capacity and length of slice b was 3, and calling append on slice b triggered the grow logic which meant that the values had to be copied to a new array with capacity 6 before attempting to append the new value. This eventually meant that original slice was not impacted by the modification.

This behavior is also the case other way around. For instance, take the following example:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

a := make([]int, 5, 6)

copy(a, []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5})

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

b := a[3:]

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

b = append(b, 10)

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

a = append(a, 20)

fmt.Printf("a: %v, cap: %d\n", a, cap(a))

fmt.Printf("b: %v, cap: %d\n", b, cap(b))

}

a: [1 2 3 4 5], cap: 6 b: [4 5], cap: 3 b: [4 5 10], cap: 3 a: [1 2 3 4 5 20], cap: 6 b: [4 5 20], cap: 3

In this case, appending the value 20 to slice a causes the 2nd-indexed value of slice b.

Conclusion

Slice type in Go is a powerful construct, giving us flexibility over Go's array type with as minimum performance hit as possible. This flexibility introduced with least performance impact comes with some additional cost of being implicit on the implications of modifications performed on slices, and these implications can be significant depending on the use case while also being very hard to track down. This post sheds some light on some of these, but I encourage you to spend time on understand how slices really works in depth before making use of them in anger. Besides this post, following resources should also help you